YERUSALEM TODAY

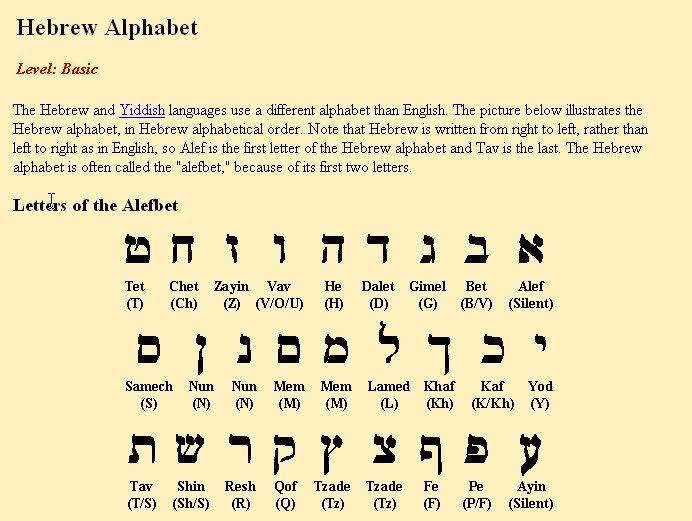

For Yahusha is The First and The Last, The Beginning and The end, The Alepha And The Tau

The Appointed Times of Refreshing are

The Seventh Day because it is the First and The Last

The New Moon, It is a first and the last day.

Seventh Day is in The Covenant, Therefore, the Covenant Bride

1 Corth 5:17 Worship

There are times of refreshing

He is faithful and just to forgive.

To cleanse ones heart with the washing of the WORD Tehillim 119:9

Prophesy means to edify. Edify means to correct aginst sin.

I think HE was indulging in the Second Passover to be cleansed even after HE died because HE observed it every year. LK 2:41

Yahusha edified at HIS Sermon On the Mount giving the fish and the loaves of bread during passover, too.

Ephesians 5:30

Wives meaning ch-rches,too...

Evangelists, Disciples, Teachers

1Cor 12:2,12-31 Submission: Seeking the better gifts.

Everyone that is baptized win Yahusha's name receives a gift of the Spirit.

Luke 24:39 http://yahwehistic.blogspot.com/2010/04/reasons-for-observing-seond-pesach.html

All religions, arts, and sciences are branches of the same tree. -

Albert Einstein

The Appointed Times of Refreshing are

The Seventh Day because it is the First and The Last

The New Moon, It is a first and the last day.

Seventh Day is in The Covenant, Therefore, the Covenant Bride

1 Corth 5:17 Worship

There are times of refreshing

He is faithful and just to forgive.

To cleanse ones heart with the washing of the WORD Tehillim 119:9

Prophesy means to edify. Edify means to correct aginst sin.

I think HE was indulging in the Second Passover to be cleansed even after HE died because HE observed it every year. LK 2:41

Yahusha edified at HIS Sermon On the Mount giving the fish and the loaves of bread during passover, too.

Ephesians 5:30

Wives meaning ch-rches,too...

Evangelists, Disciples, Teachers

1Cor 12:2,12-31 Submission: Seeking the better gifts.

Everyone that is baptized win Yahusha's name receives a gift of the Spirit.

Luke 24:39 http://yahwehistic.blogspot.com/2010/04/reasons-for-observing-seond-pesach.html

All religions, arts, and sciences are branches of the same tree. -

Albert Einstein

Symbolism Although the sixteenth century was a period of great scientific advances among European mapmakers, one of the best known maps of that period is more imaginative than accurate: a woodcut in the form of a cloverleaf, with Jerusalem depicted as the center of the world from which emanate the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa. The idea of the centrality of Yerusalem has been a mainstay in Christianity, in various ways, since its inception. It has also been integral to YAHUDIM [Judaism] since the time of King Da'ud in the tenth century BCE and, together with the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina, to Ishlam since its beginnings in the seventh century CE. In the modern era of nation-states, Jerusalem is both the capital of Israel and, for Palestinians, the capital of the state of Palestine. Thus, Yerusalem has long been a focus of powerful and intertwined passions of religion and politics. Although its name probably originally meant "foundation of [the

to mean "city of peace"(Hebr. ?卯r salom).But peace has remained an elusive goal for most of Jerusalem's nearly four-thousand year history.

In his meditation on this most Qodesh [holy] and painful city (Jerusalem: City of Mirrors, [Boston, 1989]), the "capital of memory," the Israeli writer Amos Elon observed that it is as if the very name

Jerusalem (Hebr. yer没salaim) is a reflection of the city's contradictory, even dualistic nature (aim is the Hebrew suffix indicating a dual or pair), manifesting itself even in its location on the boundary between Israel's cultivated grasslands and arid desert regions. There has always been a tension between the present and the future, the earthly and the heavenly, the real and the ideal Yerusalem [Jerusalem], a city of diverse peoples struggling to accomplish their daily activities and the city of religious visionaries.

The name Jerusalem occurs 660 times in the Hebrew Bible; Zion, often used as synonymous with Yerusalem, especially in biblical poetry, occurs another 154 times. The former appears most frequently in the historical narratives of 2 Samuel [Shemuel], Kings [Melakim], Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah [NehemYah], and in the prophetic books of Isaiah [YeshaYahu], Jeremiah [YirmeYahu], Ezekiel [Yehezqel], and Zechariah [ZekarYah] . Except for Salem in [Beresheth] Genesis 14.18, it is absent from the Pentateuch, achieving importance in ancient Israel's self-understanding only after Da'ud brought the ark of the covenant, symbol of Yahuah's presence, to the newly conquered city. The ark would find its permanent home in the Yerusalem Temple, the house of "Yod Heh Uau Heh" "YAHUAH", completed by Da'ud's son Sh'lomon, and strategically situated very near to the house of G-d's loyal servant, the king. The belief in the inviolability of Yerusalem, the chosen dwelling place of Elohim, was challenged by such prophets as Micah [] and Jeremiah [YirmeYahu], who warned that the city would be destroyed as a result of its transgressions (Mic. 3.12, quoted in Jer. 26.18). But after the Babylonian destruction of Yerusalem and its Temple in 587/586 BCE, the exilic prophets envisioned a new Yerusalem, which was simultaneously a rebuilding and restoration of the old and also an idealized city, both grander and more enduring than its predecessor, offering its inhabitants a relationship with YHUH and concomitant peace and prosperity. For Jeremiah [YirmeYahu], the rebuilt Yerusalem was well grounded in the old, even in its physical contours (30.18; 31.38-40). Yehezqel, who understood Jerusalem as "in the center of the nations, with countries all around her" (5.5), celebrates a new city and a new Temple, areas of radiating [h-liness] Qodesh, fruitfulness, and well-being (chaps. 40-48), where YHUH's

The hopes and expectations of the exilic prophets were realized in part with the rebuilding of the city and Temple during the latter half of the sixth century BCE, the first generation of Persian rule. Both, however, would be destroyed by the Roman army in 70 CE. The Temple was never rebuilt. In the generation before its destruction, the Alexandrian Jewish philosopher and statesman Philo wrote that the Jews "hold the [Qodesh] "Holy" City where stands the sacred Temple of the most high G-d [Yahuah] to be their "mother city" (Flaccum 46). The destruction of the Temple and "mother city" was both a great blow and a great challenge to

The formative texts of rabbinic Judaism, which date from roughly the third to the seventh centuries CE, share with the earlier apocalyptic texts both the centrality of the renewal of Jerusalem in the messianic age, and a lack of uniformity in the description of that future, ideal city; in some texts, an earthly Yerusalem, and in others a heavenly city; in some an earthly city that ascends to heaven, and in others a heavenly city that descends to earth. What is striking, however, are the linkages and interdependencies between the earthly and the heavenly Yerusalem. In the anti-Roman messianic Palestinian Jewish revolt of Bar Kochba (132-135 CE), the rebels struck coins with the image of the Temple facade and the inscription "of the freedom of Jerusalem," indicating their hopes for the rebuilding of Yerusalem and its Temple. Similarly, the Jewish rebels of the First Revolt (66-70 CE), with their constellation of religious, nationalist, and messianic apocalyptic motivations, issued coins with the inscription,

Early rabbinic literature did not focus only on the Yerusalem of the messianic age. The Mishnah, Talmuds, and midrashic collections celebrated the memory of the historic Yerusalem as well. Some texts describe Jerusalem as the center or "navel" of the world; others depict in glowing language the grandeur and uniqueness of the city. Yerusalem's uniqueness was reflected also in the halakhic requirements associated with the city, most of which were not practiced, given the destruction of the Temple and city, and the banning of Yahudim [Jews] from Yerusalem by the Roman emperor Hadrian, in the aftermath of the war of Bar Kochba.

As if in response to the words of the psalmist of a long-gone era, "If I forget you, O Yerusalem, let my right hand wither" ([Ps.]Tehillim 137.5), the memory of Yerusalem and its Temple and the hope for their restoration were reflected in evolving Jewish[Yahudim] liturgy, to be evoked on occasions of joy and mourning and perhaps, most importantly, to be recited as part of the Grace after Meals and the daily Amidah prayer, which together with the Shema, constitute, in a sense, the foundation of Jewish liturgy. The ninth of the month of Av developed as a day of fasting and mourning for the destruction of the First and Second Temples, becoming associated also with other calamitous events in Yahudim [Jewish] history (see, e.g., m. Ta?an. 4.6).

It is not clear to what degree and for how long Hadrian's decree banning [Yahudim]Jews from Jerusalem [Yerusalem] was enforced. "Yahudim" [Jews] were permitted to reside in Jerusalem[Yerusalem], however, during its many centuries of Muslim rule, beginning with its conquest by Caliph Umar in 638, interrupted only by the brief and, in many ways, violent rule of the twelfth-century Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. During the years of Ottoman rule (1517-1917), notwithstanding the rebuilding of Jerusalem's walls (1537-1541) by Suleiman I,Jerusalem remained a small and impoverished city. Only in the mid-to-late nineteenth century did the [Yahudim] Jews, Latin Christians, Armenian Christians, and Muslims leave their traditional quarters in the walled city to establish new ongoing neighborhoods, the Jews settling generally to the west of the Old City.

The expansion of Yerusalem outside of the walled city developed at roughly the same time as European Zionism. Many factors contributed to the evolution of the latter, including the anti-Jewish policies of the Russian czarist governments, the overall political, social, and economic conditions of Eastern European Jewry, the evolution of anti-Semitic movements and agitation in Western Europe, and the presence and vitality of other European nationalist movements. Notwithstanding the generally nontraditional religious orientation of most of the early Zionist leaders, one cannot underestimate the significance for them of Jewish historical connections with the land of Israel and the city of Jerusalem, suggested even in the term "Zionism." Nonetheless, many of the early Zionist leaders expressed a kind of 'ambivalence' about Jerusalem, reacting seemingly both to the physical squalor of the city and, from their perspectives, to Jerusalem's tired and outdated Jewish religious practices and passions. The ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities of Jerusalem were a counterpoint to the Zionists' visions of a transformed Jewish society. As late 1947, the Zionist leadership was willing to accept the United Nations resolution to partition Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state, and to make Jerusalem a separate political entity under international administration. Following the war of 1948 and the bloody battle for Yerusalem, however, neither the internationalization of Yerusalem nor the Arab state in Palestine was established. Instead, the land fell under Israeli or Jordanian rule with western Jerusalem under Israeli control and eastern Jerusalem, including the Old City and its Qodesh "h-ly" places, under Jordanian control. Yerusalem was declared the official capital of Israel in December 1949. As a result of the 1967 Six Day War, Israel began to govern formerly Jordanian-held East Yerusalem, which was later officially annexed and incorporated by the Israeli government into the state of Israel. Within the Old City stood the Western or

Although the Christian population of Yerusalem, two to three percent of the total, has been in decline for the last fifty years, the number of Christian visitors and pilgrims to Yerusalem remains very large. The roots of this fascination with Yerusalem date both to the origins of Christianity as a first-century Palestinian Jewish apocalyptic movement and to the depictions of the ministry, death, and resurrection of YAHUSHA [

As was the case with other kinds of Judaism of this period, early Christianity knew of both an earthly and a heavenly Yerusalem (e.g., Gal. 4.25-26; IBRIM [Heb.] 12.22-24). The book of Revelation, drawing heavily on

Yehezqel's vision of the New Yerusalem City,

The New Yerusalem, this Yerusalem has no Temple,

"FOR ITS TEMPLE IS YAHUAH ALMIGHTY AND THE LAMB"(21.22).

As Robert Wilken has noted, speculation concerning Yod's future kingdom on earth with Yerusalem as its center dominated Christian eschatology of the first and second centuries, as, for example, in the writings of Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. Later ch-rch fathers, however, such as Origen, who spent more than twenty years in third-century Caesarea, disputed both the teachings of Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, as well as Jewish beliefs in the future restoration of some kind of Yerusalem on earth, to speak only of the heavenly Yerusalem, which remained above and entirely separate from the earthly city.The fourth century was a period of tremendous change for Christianity. It entered the century as the religion of a persecuted minority, and exited as the official state religion of the Roman empire. Emperor Constantine made Christianity a legal religion in 313, and became its patron and protector Palestine and in particular Yerusalem became a Christian showplace of sorts. From the time of Constantine, massive ch-rch building projects were undertaken to create a visible and

Christian pilgrimage to Palestine and especially Jerusalem became widespread in the fourth century. Early pilgrims included Helena, the mother of Constantine. Fourth-century Christian pilgrims, as part of their quest for perfection, would undertake the dangers of travel to Palestine to visit the 'H-ly' places, and therein both confirm and strengthen their faith. As pilgrimage flourished, some ch-rch leaders questioned its value, drawing attention to the contrast between "Jerusalem the H-ly" and the city "Yerusalem the Qodesh" that awaited the pilgrim. For example, Gregory of Nyssa in his "Letter on Pilgrimage" pointed to the "shameful practices" of the people of Jerusalem as evidence that 'God's' grace was no more abundant in [Yerusalem]Jerusalem than elsewhere.

Echoes of early Christian speculations on the role and nature of[Yerusalem] Jerusalem in the end time, as well as an interest in the earthly city itself, can be found both in the constellation of factors that shaped the Crusades of medieval Europe, and in the voyages of Columbus who, influenced by late fifteenth-century apocalyptic thought, sought to acquire the gold to finance the final crusade, which would capture Jerusalem and place it again in Christian hands-all part of G-d's plan for the end time.

Columbus failed in his plans, but Christian interest in and pilgrimage to [Jerusalem] Yerusalem has endured. For many pilgrims, the

Although an overview of the symbolism and significance of Jerusalem for Islam is beyond the scope of this article, one must note both the importance of Jerusalem for Islam, and the importance of the city's Muslim communities since their inception in the seventh century CE for the history of Jerusalem, in Arabic "al-Quds," "the Holy." Today, Jerusalem's major Muslim Holi place, the magnificent

The sanctity for Ishmel of the 'Rock', the Haram, and Yerusalem, in general, was strengthened by the identification by night journey (Surah 17:1), and "the Rock" as the place from which he ascended to heaven (Surah 53:4-10). As in YAHudaism and Christianity, Yerusalem assumed an important role in Muslim beliefs concerning the end time and the day of judgment. So too, Muslim sources reflect the tensions between the

Yerusalem is today a city of approximately one-half million people, a city which both celebrates and is haunted by its history, a city in which the tensions between the ideal and the real Yerusalem are lived and witnessed daily, and in which the rages and passions of religion and politics bring to mind the words of the psalmist,

"Pray for the peace of Yerusalem" (TEHILLIM [Ps.] 122.6).

-JMCOFFEY

Work Cited:

Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, Barbara Geller Nathanson "Jerusalem: Symbolism" The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. Oxford University Press Inc. 1993. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. JC@YAHUSHAREIGNS.COM Pellissippi State Technical CC. 23 March 2010

Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, Barbara Geller Nathanson "Jerusalem: Symbolism" The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. Oxford University Press Inc. 1993. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. JC@YAHUSHAREIGNS.COM Pellissippi State Technical CC. 23 March 2010